focus on latin american photography

Text by Angie Carrillo Torres

Since the 1970s, Latin American photography has been recognized as an artistic expression, as a category. But the truth is that this label barely reflects the surface of Ibero-America's rich and diverse visual identity. Despite sharing common narratives and challenges, each country, each community, even each corner, has its own distinctive culture and aesthetic.

Today, contemporary Latin American photography manifests itself mainly through three axes. First, there are the imaginaries and memories that are woven into stories saturated with history and social commitment. These are, without a doubt, a tool of denunciation that exposes the multiple waves of violence and conflicts that have left their mark throughout the region. In the second axis, which comprises aesthetics and anthropologies, are visual elements that define national identity and ethnography; elements that can only be understood through cultural patterns. In the third axis, photographic practices such as photojournalism, portraiture or documentary photography are explored and developed (Monteiro and Leiva Quijada, 2015).

In this context, it is key to understand that while Latin America shares similar cultural visions in its photography, its most relevant element is the individual experience. The source of inspiration, ideas or concepts can come from any place or situation, guided by the artist's interests, and can be expressed in thousands of unique ways. Here see-zeen presents work by ten Latin American photographers who not only create unique narratives, but narratives that seem to be connected to each other.

Marisol Méndez’ series Madre (Mother) highlights the presence of women with elements that are byproducts of colonization. She shows religious traits that symbolize what it means to be a woman in Bolivia (especially through the representation of the Virgin Mary or Mary Magdalene). Her photographs question this religious vision and satirically expose “purity” as an emblem of femininity, which is clearly a social imposition. One can see in her work experiences of Latin American women, such as quinceañera, the celebration of a girl’s 15th birthday.

As a Latina woman I lived each of these stages following cultural and family practices, and only now I could see their impact, realizing that many of these things actually caused conflict with my identity, with my way of relating to society and above all, with the questioning and search of my spirituality. For this reason, it is fascinating to see in this work photos that show the contrast and oppose the traditional and patriarchal Latin perspective.

©marisol mendez

Mendez states that she is not afraid to make her photography political or to address social situations. In her work she also denounces other issues, such as the climate crisis or class inequality.

Her collaborative project with photographer Monty Kaplan, titled Miruku, highlights both issues located in the northeast of Colombia in the department of La Guajira, where there is a worrying shortage of potable water that mainly affects the Wayuu indigenous community. The project is a call to action to address this unacceptable situation that disproportionately affects vulnerable communities. Lack of access to a basic resource affects people's health, education and quality of life.

©marisol mendez and monty kaplan

Monty Kaplan's solo projects also examine how human neglect has ravaged their habitat; Paraíso (Paradise) for example, tracks the remnants of forest fires in the Iberá wetlands of Argentina. But Monty doesn't just explore these kinds of themes. He also includes fantastic and surrealistic perspectives, as is evident in Un accidente (An Accident), where the double exposure of some photographs illustrates the memories or the uncertain and diffuse hallucinations of a character.

©monty kaplan

Cultural connotations can be seen in the work Tonatiuh by Juan Brenner, who explores the characteristic features of today's Guatemalan, showing it as the result of European influence since colonization. He also emphasizes the image of the conquistador Pedro de Alvarado, who managed to take over a large part of the Central American region, and how he represents a role model that continues to wreak havoc in the contemporary collective imaginary of Guatemalans. This obeisance to the foreigner has fostered the insertion of power structures, a national identity crisis and inequality. This can be observed in the images where gold teeth have become identity traits. Or as is the case of the images where the figure of Mickey Mouse shows the traces of globalization.

©juan brenner

Returning to the ecological and environmentalist sense embodied in Miruku, the work of Sofía López Mañán stands out with her series El rey pájaro (The Bird King) and El libro de la naturaleza (The Book of Nature), in which she expresses her concern for the environment. The first series questions the relationship of human beings with nature through photographs with a chimerical aspect. Her photograph of a tiger perching on a bed, interrogates the awareness of the unexplored link between human life and the life that inhabits the natural environment. The second series expresses concern for the animal world, especially the Andean condor and how the human carbon footprint has brought this species almost to the point of extinction. Both series invite everyone to reconsider their role in preserving the environmental balance.

©sofía lópez mañan

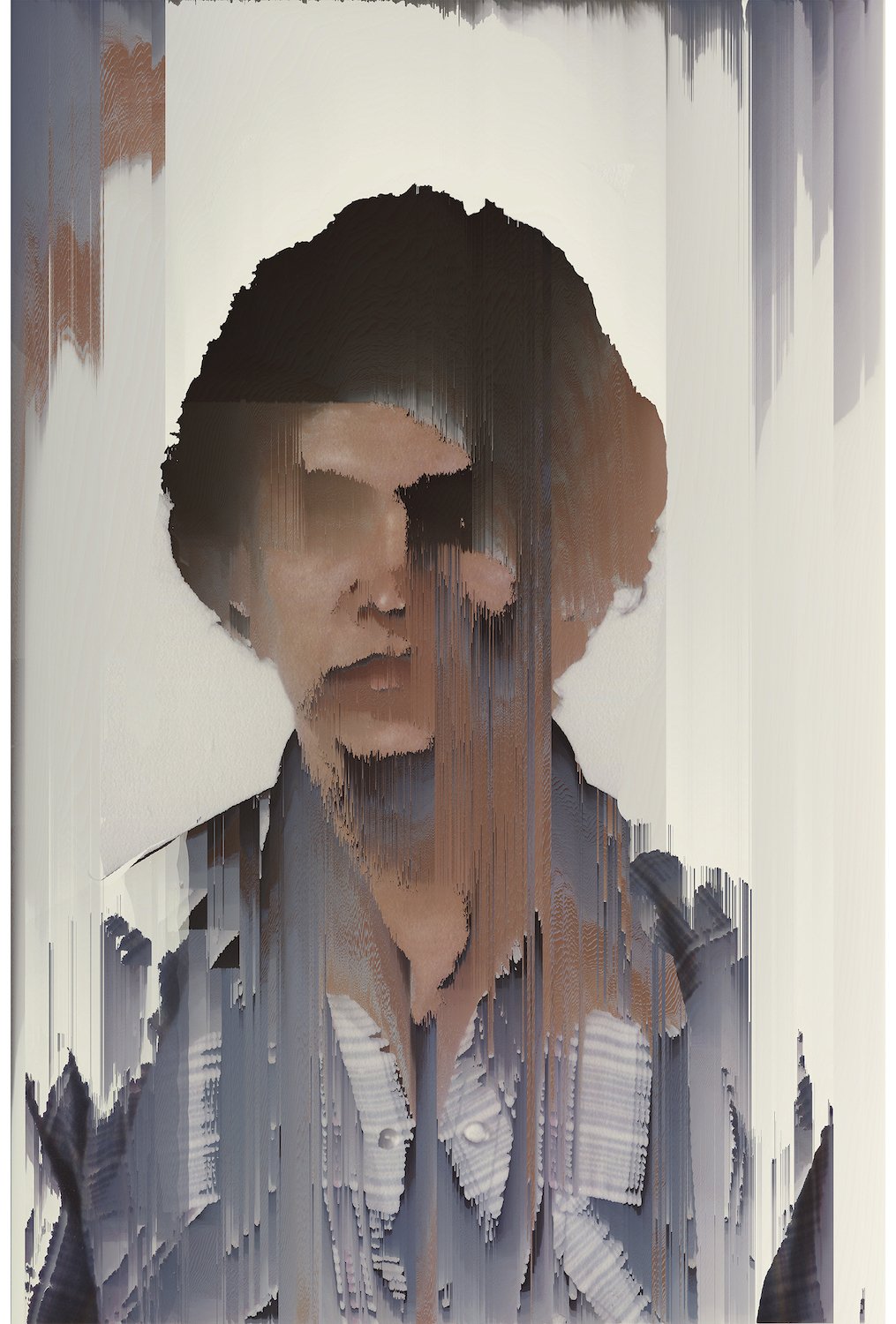

From these series one can begin to understand a little more about Latin American reality. However, it is fundamental to see how these occurrences permeate the individual experience and how certain personal events make catharsis in art. This is the theme of Cristóbal Ascencio's work, who perhaps found in his most intimate side the catalyst for his photography. His series Las Flores Mueren dos Veces (Flowers Die Twice) arises from a significant and very painful episode: the suicide of his father, which he learned about fifteen years after his death. Different strategies of digital manipulation were the means used to express the concept of “memory distortion”; a visual analogy that symbolizes the mutation of memories. Ascencio questions himself about the paternal figure he thought he knew, and his confusion is reflected in each photograph he intervenes in. Its main feature is the "glitch" - seen in the photo of his father reflected in the glass - which builds an internal dialogue that shows the duality of his father's personality. On the left is what Ascencio knew and on the right is the blurred reality; the sincere but absent reminiscence. In homage to his father, who was a gardener named Margarito, Ascencio has digitally constructed images of flowers with the apparent purpose of communicating with him, as well as re-signifying his history and his true nature.

In a similar way, in his series Instant Fossils, the characteristic distortion of the pixels is once again the protagonist. In this case, the meaning of the image lies in those found and practically abandoned objects that have become superfluous in the landscape.

©cristobal ascencio

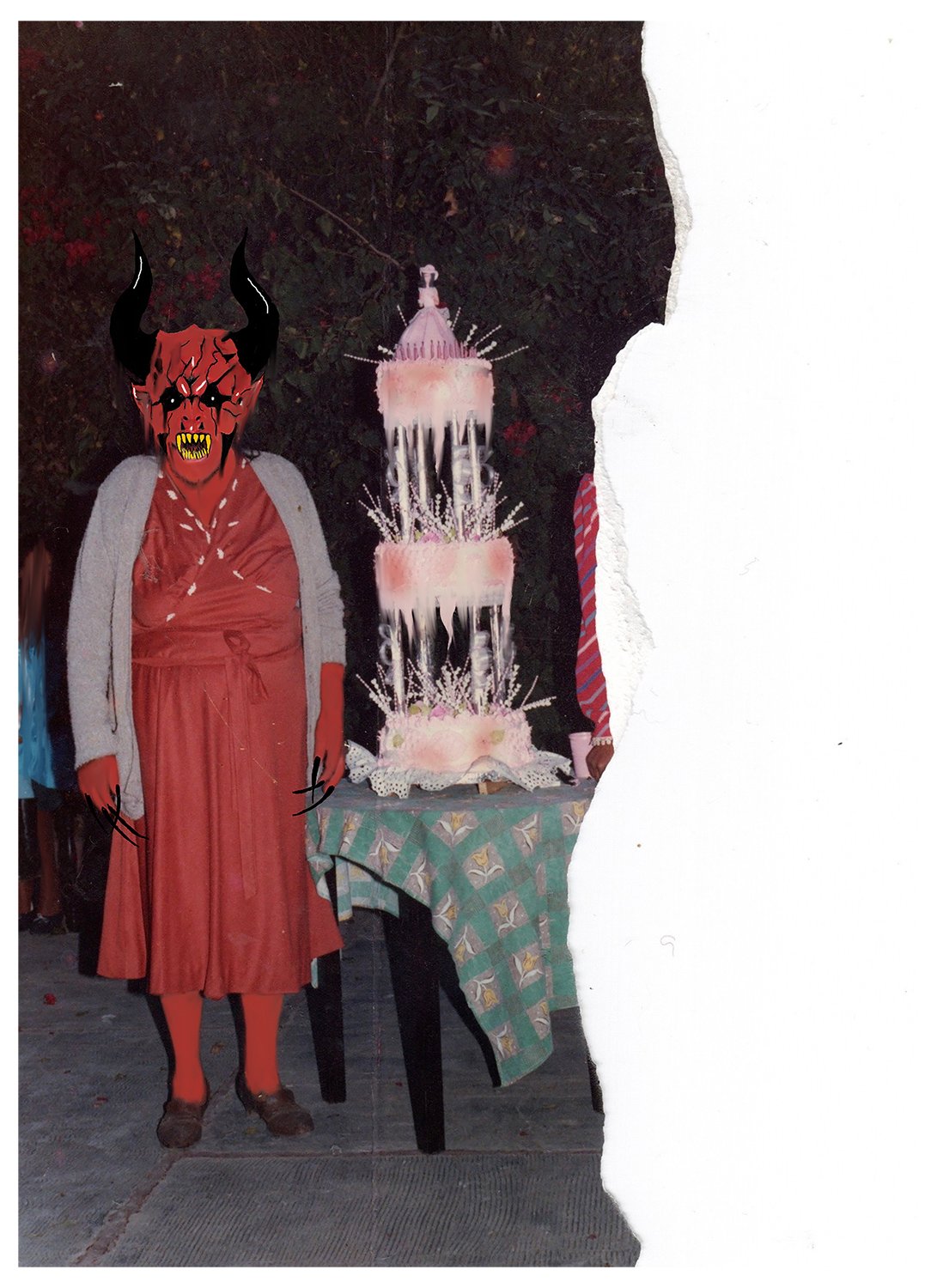

Another example of photography as a mechanism to materialize and immortalize memories according to the artist's gaze, is the work of Diego Moreno in Influencias Malignas (Malign Influences), where he analogically transforms family memories into monstrous-looking images. These images are based on an apocalyptic vision of Catholic aesthetics and religion (elements deeply rooted in Latin American culture), like the photograph of five people whose faces have been transformed by the artist and are depicted inside of what appears to be a church or chapel, giving the photograph an even more somber appearance. It is also not uncommon for certain religious symbols to be seen from a dark and macabre perspective, especially in Latin America, where the strong imposition of belonging to this religion is traumatizing for some who end up rejecting it. And while Moreno's art may seem to some to be an act of extreme rebellion, the reality is that these “evil” creatures are actually a kinder representation of themselves.

The inspiration for these creatures comes from the violence and rejection Moreno experienced as a child because of his sexual orientation. He grew up in a macho and homophobic household, full of taboos and hostility so those things that were different and disruptive seemed to resonate more with his identity and image. Also, the presence of his aunt Cati led him to redefine the value of what is considered “different” as she too was rejected and mistreated by her family for looking different due to an autoimmune disease. The transformation of family memories, (as is also in the case of Ascencio), is not only an artistic manifestation, but also a strategy for healing and self-reflection.

©diego moreno

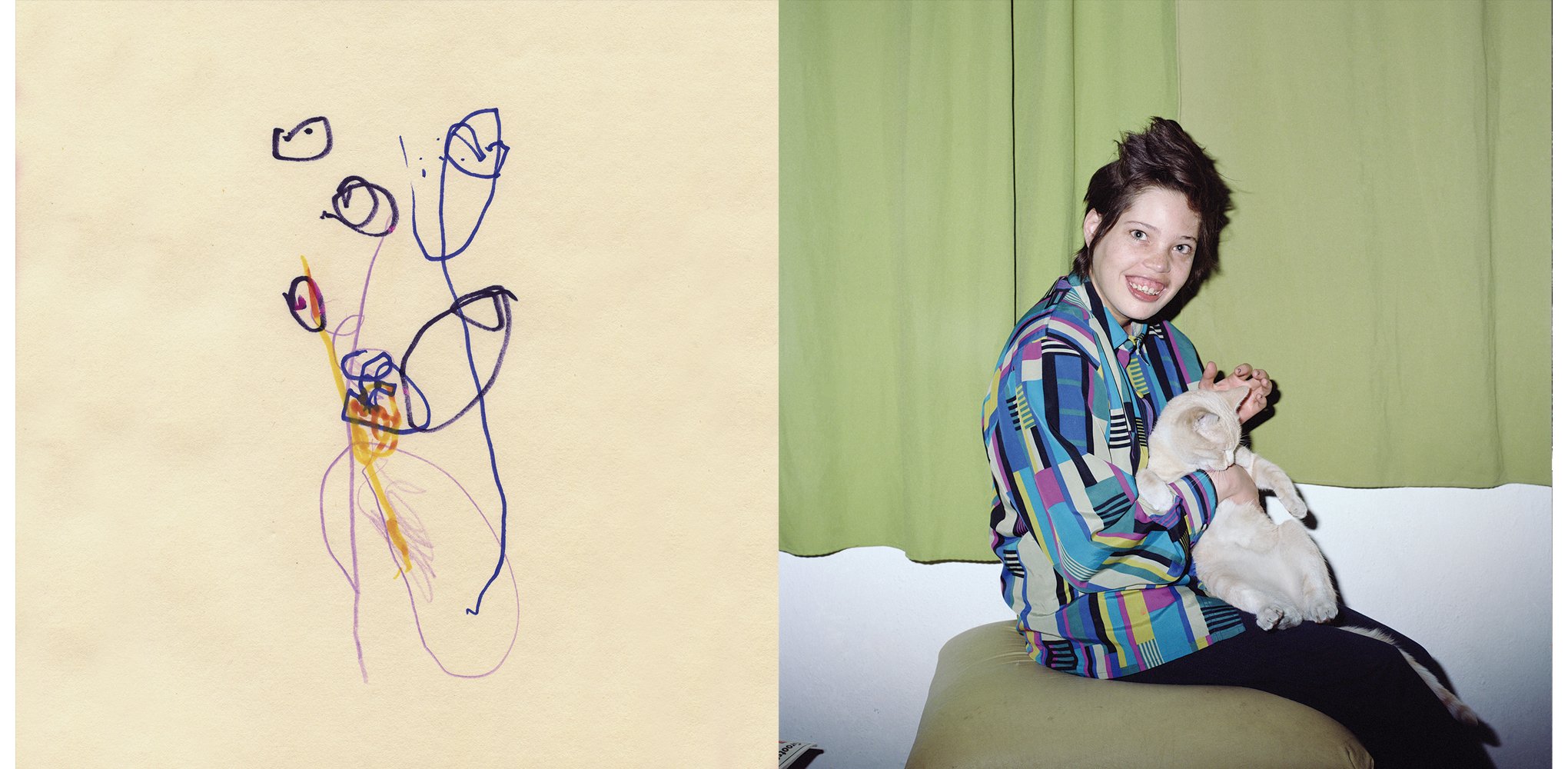

The work of Fabiola Cedillo similarly explores the experience of “the misunderstood”. In her photographs she is not the protagonist of the story, but her older sister, who suffers from an advanced case of epilepsy, is. With this work one can glimpse a Latin American side, which sadly seems to be linked to feelings of pain and affliction. In Los mundos de Tita (The Worlds of Tita) Cedillo presents a series of vivid and colorful scenes. It is a kind and pleasant vision of her sister's mind that does not pretend to be shown with pity.

Perhaps the most touching photographs are those that depict objects from Tita's childhood. The pink tones speak for themselves, capturing the innocence and the stage in which she has always lived. Striking is the duality of the diptychs in which these childhood objects are shown next to a photograph of Tita with slightly tired and even blank eyes, which is disconcerting when compared to her smiling and comical portraits.

Los Mundos de Tita is an intimate series that leads the viewer to feel connected with the fantastic mind of a stranger that allows us to know a little of her way of seeing the world.

©fabiola cedillo

With an ethnographic and anthropological perspective, Fernanda Liberti's work Dancing with the Tupinambá aims to give visibility to the Brazilian indigenous community, focusing on the history and importance of the Tupinambá mantles; feather ornaments that represent an entity and were stolen mainly by European colonizers. In her photographs there is not only a cultural emphasis, but a unique connection to the nature and spirit of the area. In this series Liberti vindicates the voice of the community, especially the voice of Glicéria, giving them the opportunity to express their resentment towards the violence they have experienced since their origins, but also to convey gratitude and freedom. The photographs that most capture that symbolism are perhaps the images captured from overhead.

©fernanda liberti

There is a non-implicit link between Dancing with the Tupinambá and the series Origen (Origin) by Glorianna Ximendaz. The connection is what has been stolen from them. For the Tupinambá it is not just a mantle, but their dignity, which for Ximendaz and the women of her family has also been taken from their hands. Ximendaz recounts through her photographs the patriarchal violence that her maternal lineage has been forced to live with. Thanks to these photographs, the rage and pain of her family is released, as she manages to condemn all those who have exercised some kind of violence against her condition as a woman; which is not only a reality for the artist, but also for us women in Latin America and the world.

A heroic act performed by the artist is the decision to show the faces of the abusers, as can be seen in the image revealing the identity of the rapist of her great-grandmother, accompanied by the following description: “Flaming photograph of the military dictator and former president of Costa Rica who raped and impregnated my great-grandmother, after that, she was threatened to prevent her from speaking. She had to escape because she worked as his maid.” And why is this a heroic act? It is heroic because for many women, their stories and their aggressors remain forever in the shadows, while they are granted impunity and the benefit of silence. That is why Ximendaz not only gives relevance to a cause of utmost importance but also allows, as in the case of Ascencio and Moreno, to end the cycle of pain.

©glorianna ximendaz

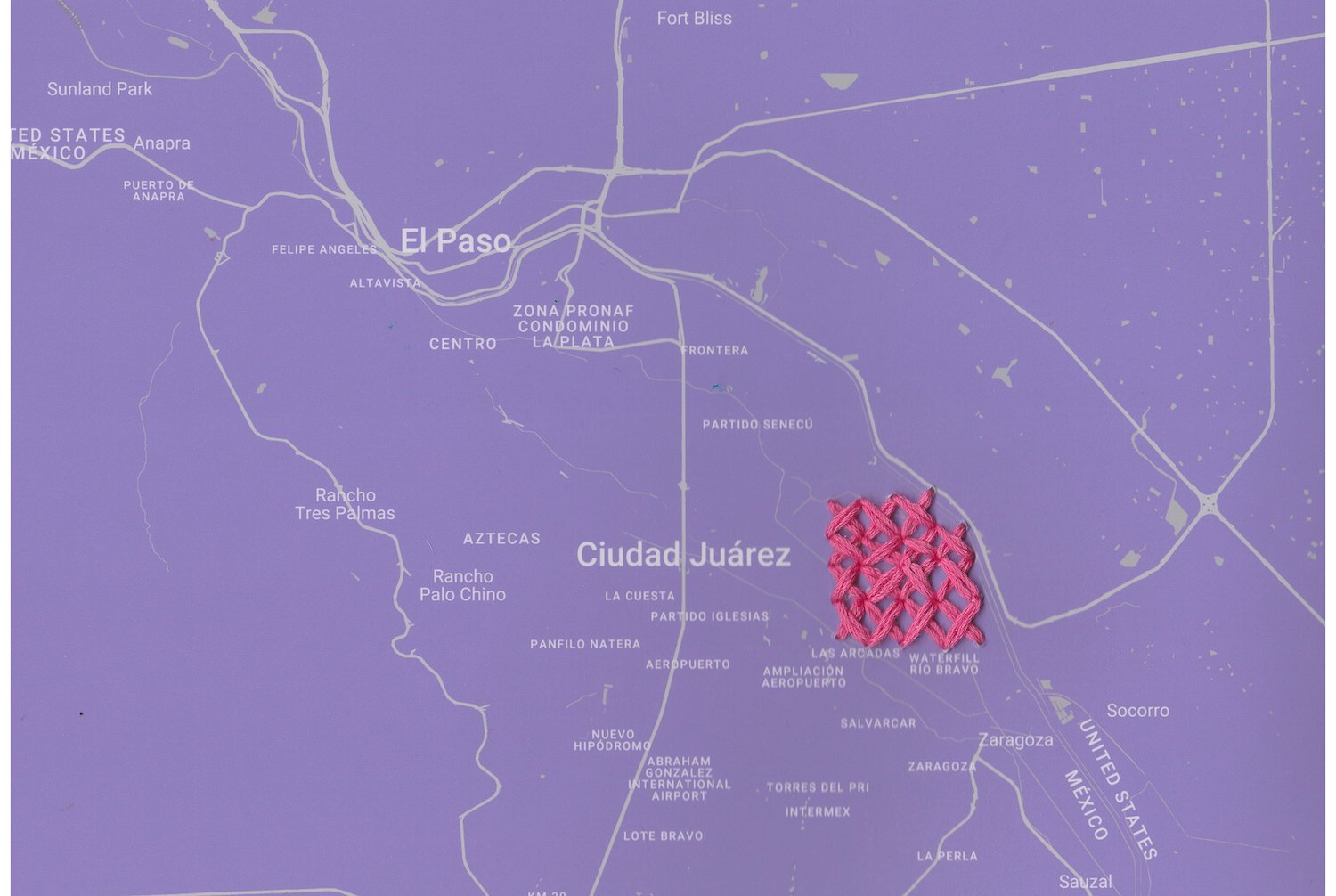

Another Latin American reality is seen in the work of Persia Campbell, who narrates her own experiences living in border areas such as Ciudad Juarez and El Paso (Mexico) in times when the drug war between cartels took away the peace of the region. Isolation was a coping mechanism used by residents of the area to protect themselves from the harsh reality seen on the streets. Campbell expresses this in both Reminiscencias de Ciudad Juárez (Border Reminiscences) and Itinerario de una Mujer en la Frontera (Itinerary of a Woman Along the Border), exalting the mise-en-scène with colorful tones, while in small details she added the flashes of reality, thus generating a division between the real world and the fictitious paradise that people used as a consolation for their desperate situation. One of her images portrays Campbell's "quiet" life while ignoring the television news.

©persia campbell

This journey through stories, images, memories, concepts and values opens the door to a small part of Latin American culture. Ironically, all these projects coincide in one thing: pain as a creative resource. Pain here is the product of violence and personal experiences. It is the result of a process of colonization, inequality and discrimination. It is the product of machismo, prejudice and taboos. It is the consequence of mistreatment of minorities and damage to nature. However, these problems do not constitute Latin America, but are realities that have been expressed by the voices of artists very committed to denouncing and telling the truth.

Works Cited

:

Corp, Mathieu. “Experiencias del tiempo en la fotografía latinoamericana contemporánea.”

Hal Open Science, 2016.

Charles Monteiro and Gonzalo Leiva Quijada. “Fotografía en América Latina”

”Contemporánea.” Arteologie - Recherche sur les arts, le patrimoine et la littérature de l'Amérique latine, 2015.

Cristobal Ascencio - Mexico

Website

Instagram

News: Cristobal’s work is currently showing at the Regenerate Noordelicht Photography Festival in the Netherlands till December 10, 2023 and at Imaginaria Festival in Benicassim, Spain until December 10, 2023 .

Juan Brenner - Guatemala

Website

Instagram

News: Juan’s work is part of a group exhibition El Dorado, Myths of Gold at the Art Americas Society in New York until May 18, 2024

and in the exhibition Rumiante at Segismundo opening December 6, 2023 until March 8, 2024 in Guatemala City, Guatemala.

His books Genesis and Marvelous Phenomena will be released in 2024.

Persia Campbell - Mexico

Website

Instagram

News: Persia’s first solo show opens November 25, 2023 at Almanaque Fotográfica Gallery in Mexico City, Mexico.

Fabiola Cedillo - Ecuador

Website

Instagram

News: Fabiola’s solo exhibition The Future curated by María Fernanda García opens December 8, 2023 at the Cultural Epicenter: Casa Rivera in Cuence, Ecuador.

Monty Kaplan - Argentina

Website

Instagram

Fernanda Liberti - Brazil

Website

Instagram

News: Fernanda’s work will be shown at the Indian Photography Festival, State Gallery of Art, Madhapur, November 2023 - January 2024

and at the MUDEC Museo delle Culture in Milan opening in December 2023.

Sofía López Mañan - Argentina

Website

Instagram

News: Book release in 2024

Marisol Mendez - Bolivia

Website

Instagram

News: The book Madre was recently published by Setanta Books.

Marisol will be signing copies of the book at Polycopies in Paris November 9, 2023.

Diego Moreno - Mexico

Instagram

News: Diego will be part of the exhibition Mexichrome. Fotografía y color en México at the Museo Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, starting November 28, 2023.

Glorianna Ximendaz - Costa Rica

Website

Instagram

News: Glorianna’s work is currently on show at the Regenerate Noordelicht Photography Festival in the Netherlands till December 10, 2023.

Her work is also part of Indian Photo Festival in Hyderabad from November 23, 2023 till January 7, 2024.